Adolescence: The “Ghost” That Haunts Parents and Educators

According to the literature and our own experience, human life is often described in stages: infancy, childhood, pre-adolescence, adolescence and adulthood.

Each stage has its own characteristics, depending also on what we take in from our environment. The transition from one stage to the next also matters a great deal—those so-called transitional periods in life when we are asked, in a sense, to leave parts of ourselves behind and keep moving forward, while gaining new perceptions and experiences. These stages often do not have clear borders; elements from earlier stages can still be present in our current situation, whether we recognize them or not.

In general, it is considered healthy to recognize in ourselves any leftovers from earlier stages of our life, positive and negative, as part of a desired self-awareness.

How we learn to handle the transitional periods of our life is a matter of many layers of learning and, of course, a safe setting: when the setting is safe, we have the chance to “educate” ourselves, in the sense of recognizing both the positive and negative sides of our character, in the process of self-awareness we mentioned.

One of these stages is adolescence, which typically shows its first signs around ages 11–13 and winds down around 15–17. Like all developmental stages, it is influenced by many factors and can be experienced and understood on many levels. Adolescence often worries and unsettles adults, with consequences that can sometimes be serious for the young person and those around them, literally “turning things upside down” and affecting everyone involved: peers, parents and family, and educators.

We ourselves have likely been involved as teenagers, as parents or as educators in this transitional period, and it often leaves us with questions: parents look to the school and staff for help, while educators, having tried many approaches, often find it hard to manage the adolescent classroom.

From this reality a series of questions arises. Here we try to answer some of them:

- Is someone to blame? And if so, who?

- What can we do ourselves (as parents and educators) for adolescent children and students?

- Could the adolescent’s reaction be directly related to our own reaction?

- Is there a way out when a situation becomes dangerous? (e.g. substance use, extreme behavior, aggression)

Is Someone to Blame? And If So, Who?

As we said in the introduction, adolescence is a time of transition. If we ask those directly involved the first question, the answers are often what we might expect, and we partly see people pointing the finger at each other. If we ask educators, they may say: “Of course the child isn’t to blame, it’s the family—everything starts from there,” adding “We’ve tried to reach the family, we can’t communicate easily,” “they don’t speak the language,” “we can’t get hold of them by phone,” “we’ve invited them and they don’t come,” “they work and can’t come to school to talk.”

If we turn to parents who are seeking help, they tell us: “Family is very important, but shouldn’t the school do something too?”, “My child is being treated unfairly; their behavior has improved and it’s not being acknowledged,” “So-and-so teacher has it in for them,” “We don’t have much time with our child—we both have to work, and anyway they’re older now,” “Please, let’s do something together; things have gone too far.”

If we turn to the young person who is looking for help and for someone to understand their behavior, they might say: “They’re always picking on me,” “They don’t see how hard I’m trying,” “I can’t study, I’m bored in class,” “They told me to do it [an extreme behavior] if I’m brave enough,” “I’m scared,” “My parents don’t understand me.”

So when we consider all sides, we see that blaming one another makes little sense, because simply put, no one is solely “to blame.” In fact, everyone has some valid point.

What matters most is to understand all sides so that we can handle the situations that arise during adolescence—and that in itself helps create a safer environment for the adolescent.

What Can We Do Ourselves (Parents and Educators) for Adolescent Children and Students?

We have already begun to answer the second question. Understanding on the part of parents and educators is the first step in this effort. In practice, understanding can be fostered with simple tools, such as opening the door to communication and active listening and empathy. That is, we pause our own thoughts for a moment so we can hear the other person, and we give ourselves almost fully to that act of listening.

Active listening also includes observation: we talk, we let the young person speak, we don’t interrupt (and we kindly ask that they don’t interrupt us either), and we notice what they say, the depth that may have gone unheard until now, their feelings, their body and their eyes.

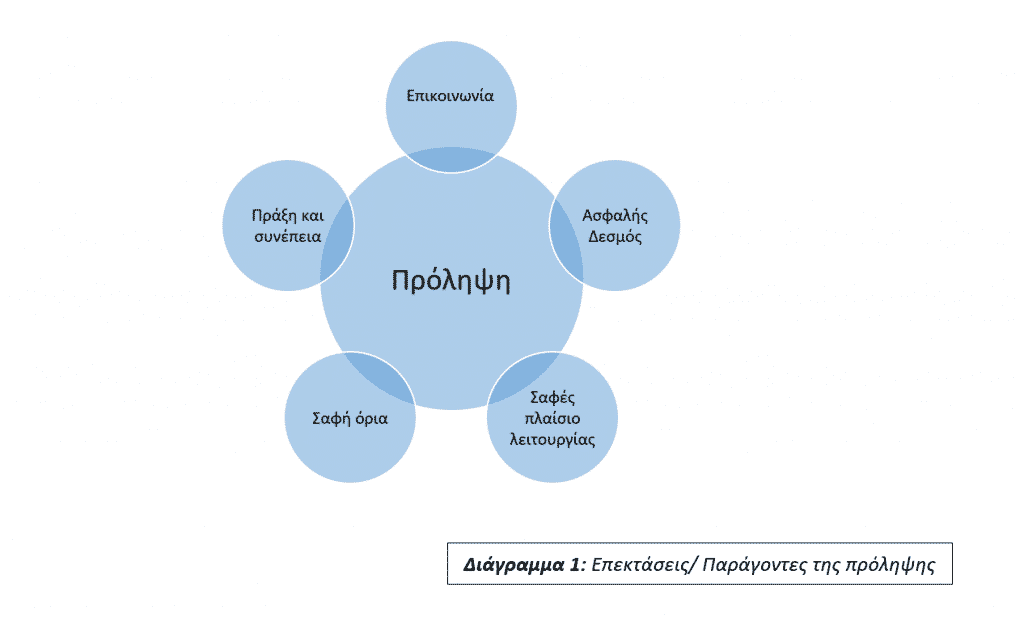

As adults we have the chance to create a safe space for communication, with clear boundaries, in which the adolescent can open up without feeling threatened. Of course this is an ongoing process; it isn’t done in one conversation but in a continuous one, whenever the young person or we need it. And most important of all, this communication and this safe bond and setting are best built before a crisis—as the best form of prevention, which can truly save lives.

Could Their Reaction Be Directly Related to Us?

Here we come to our third question: whether the students’ reaction might be connected to us as well—for example in an argument. Often parents and educators feel overwhelmed because they have tried many ways to handle situations, frequently in this order: “at first I was gentle, but I didn’t see any improvement; when I became stricter, things got worse and we lost all communication.”

One key difference between adolescents and adults is the experience that adults have and that adolescents, by nature, do not yet have.

As adults we have often noticed that when we don’t fuel an unwanted behavior with our reaction, it often fades. So during a clash, when the adolescent is angry and we acknowledge their feeling but don’t let it pull us in, the emotion tends to ease. If we get angry too, we step into that same “emotional river” and it becomes very hard to step back out.

But because we are adults, we have the experience to choose not to get caught up in the anger of the moment. And as “teachers” of our children—whether they are our students or our own kids—we need to stay on the shore, without of course leaving them alone to “figure it out.” We accompany them on these short “trips” of anger but show them, in our way, that we will talk when the strong emotion has calmed. That we are there for whatever they need. Because whatever happens, they are our children—our flesh and blood—or our “mind-children” as educators and teachers.

Is There a Way Out When a Situation Becomes Dangerous? (e.g. Substance Use, Extreme Behavior, Aggression)

We come to the fourth and very important question: Can we turn things around when they have gone too far? In short, the answer is that we often can—but sometimes it is not possible, especially when things have moved onto genuinely dangerous paths. When a situation is already tense, the balance is fragile and our next move can have serious consequences.

Every situation is different, as are the people in it. There is no single fix for every difficult situation an adolescent may be in, but standing by the young person and the student as we described above—starting without judging, and being ready to listen—certainly helps.

How we handle a crisis depends directly on how we have learned so far to communicate with that person, the trust we have built, the secure bond, the boundaries and the way we usually work together. In short, in a crisis, if we haven’t done prevention, the difficulties can be very great. At the same time, having done prevention in our family, in our class or in our relationships doesn’t mean that an unexpected situation will never appear. It does mean we are better prepared to face it, because we will have “armored” ourselves early on.

Below is a short example—a dialogue that can shake a family system. What matters is to focus on how the mother responds.

Example of a Family That Has Worked with Prevention

“I could see that S. had been acting strangely for a while. He was never a top student, but his father and I always tried our best—above all that he behave properly toward us and others. From the start of the year his behavior had changed. He was coming home late and missing the first periods at school almost every day. Sometimes he skipped tutoring, but I always heard it from him before the tutors told me. Thankfully we’ve built a good relationship over the years; we talk a lot and he confides in me. We have our outbursts, but he always feels safe and comes back to us, to our home. A week ago I asked him:

– Is everything okay? (opening the door to communication)

– Yeah, everything’s fine!

– I’ve noticed you’ve been a bit off lately, that’s why I’m asking.

– Yeah Mum, it’s fine, don’t worry. It’s just that lately we’ve been hanging out with … and we’re having a great time! They’re good kids. Because we’re having fun, that’s why I get home late.

– You know you can tell me anything that’s bothering you. (reminder of the safe space that’s already there)

– Yeah Mum, thanks a lot!

– There’s something that’s bothering me too. It’s your absences at school. I know you’re having fun, but I think you need to hold up your side as a student too. Let’s talk about it.

– Yeah I know, I’ve thought about it too! But what can I do—it’s the first time I’ve felt so good in a group, and I can’t just leave them and go home early. They’ll call me a loser! (influence of peers)

– Okay, let’s find a middle ground. I have some ideas to discuss—want to hear them? (or “give me a moment to think…”) Ready to listen?

– Yeah, go on…

– I suggest you go out together on Friday and Saturday when you don’t have school the next day, but you text me where you are and that you’re okay. You can’t come home at 3 a.m. like you did the other day! On other days either you’re back by a set time—say 10 p.m.—so you can rest, or your friends come here. You can hang out in your room. That’s what I suggest; what do you think?

– I don’t know, sounds okay. But having them over here… I don’t know…

– … (she lets him talk, observes him, listens actively, stays silent. Why doesn’t he want his friends to come to the house?)

– Um, Mum… I don’t know…

– Tell me, S. I’m listening, I’m here for you. You know that whatever you tell me, we’ll try to work it out together. I’m on your side. (active listening, safe bond, communication)

– I can’t say it… I mean, how do I put it…

– …

– You know I smoke a bit, always outside the house.

– Yes S., I know and we’ve talked about it quite a bit.

– It’s just that G. and N.—they’re brothers—and now their cousin’s been here for two weeks and we’re all hanging out. He suggested we try marijuana and we did.

– When did that happen, roughly? (she approaches him with care, doesn’t load the moment with her own reaction despite what she heard, tries to stay steady)

– About ten days ago.

– And? (despite her shock, the mother doesn’t lecture yet. She knows it’s better to talk when she herself is calmer)

– We liked it and we’ve been doing it almost every night. I don’t do it every time but I’ve tried it quite a few times.

– You know you need to be careful, right? We’ve talked about addiction in general, and about cigarettes and alcohol. It’s very easy to go from trying to using to misusing. (prevention has already happened; they’ve discussed addiction in general)

– (he starts to cry)

– Sweetheart, why are you crying? We said we’re in this together, whatever happens. (reminder of the family’s safe framework)

– Mum I’m scared—I think I’ve already moved from trying to using. (he recognizes his feeling and shows self-awareness; he sees the consequences of his actions)

– Don’t be scared, we’re together, we’ll find a way. (the safe bond in action)

– I love you so much Mum!

– I love you too, S.! (They embrace; emotions are expressed.)

…”

In this example it is interesting to see how the visible “symptom” (absences from school and late nights that disrupt the student’s life) is one thing, and the real problem another. Imagine a family that, based only on this visible behavior, grounds the student for a week “to teach them a lesson.” The young person may pay a price for their actions, but the family may never learn that their child has been using substances—and what the young person does after the punishment, in relation to that use, remains uncertain. The possible consequences for the family can be very serious. The child may cut off all communication with the family and get caught in a cycle of use, while for years they may be searching for what was really missing.

In all cases it is a good idea to consult a third party—a professional (e.g. social worker, psychologist, educator) whom we trust and who can offer us alternatives for how to proceed. Often we cannot act alone and we need a second or third “pair of eyes,” because when we are living inside a problem we are emotionally involved, and our feelings can distort our clear view of the situation.

So don’t hesitate to share what is troubling you, with care and with the right people. Those professionals and the people you talk to should be bound by confidentiality and as objective as possible (not caught up in the problem): these are some of the first basics for a good start in dealing with a difficult situation.

For more on how we grow through life’s stages and how to support young people in difficult situations, read our articles The Psychosocial Development of People and Let’s Talk About Bullying.

Happy Life Team